Many shoulder exercises overload the top of the movement, a weaker position with less tension for building muscle.

This overload happens on various raises when the dumbbell is furthest away from your shoulder, forming a descending strength curve. More torque is needed to prevent rotation, or your arm from falling, versus other portions throughout the range of motion.

Unfortunately, the myofilaments responsible for contraction bunch up here, since the muscle shortens utmost, meaning fewer cross-bridges form to create tension.

As you continue higher with the dumbbells above shoulder level, upward rotation of the scapula dominates, focusing on the serratus and trapezius.

Despite this all, we shouldn’t overload the deltoid at too low an angle. This changes its moment arm, or the leverage the whole muscle has at the shoulder, instead favoring the rotator cuff muscles. The moment arm is more important toward force potential than muscle length.

Therefore, overloading the glenohumeral joint at the midpoint of possible movement, about 45°, creates better exercises for the deltoid. How we achieve this differs by which head we target…

Side Delt: Incline Dumbbell or Cable Lateral Raise

Overloading the midpoint can be achieved in a few ways, which mostly requires working a single arm at a time:

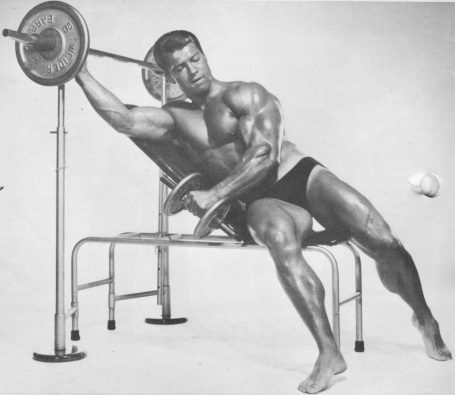

- Lie on your side across a 45° incline bench, or lie across a flat bench then prop yourself up using the non-active arm.

- Lean significantly against a wall, striving for about 45° with your body relative to the wall.

- Use a cable pulley machine, having the cable angled at 45°.

The last option has the advantage of a small handle versus the plates of a fixed or adjustable dumbbell, which can make the movement a bit awkward while limiting the stretch.

Keeping the weight close to you allows purer abduction that emphasizes the middlemost deltoid fibers. Going behind-the-back allows a deeper stretch as well.

Due to moment arms, the supraspinatus of the rotator cuff dominates up until 15°. This may seem to make a lying side lateral raise on a slight angle more suitable, but too much range of motion overloading this muscle could have it fail before the deltoid fatigues.

Cheating the weight up at the bottom of the movement does help, suggested by the legendary Larry Scott, since it favors overloading the deltoid over the supraspinatus.

Stopping at 45° limits upward rotation, which hits the serratus anterior and lower/middle trapezius. Otherwise also includes some upper trapezius from shoulder elevation. The overhead press works better for upward rotation.

Upper trap development is not ideal toward developing a classic physique, since overdevelopment here may detract from the illusion of shoulder width.

Rear Delt: Lying Dumbbell or Cable Lateral Raise

Using only a single arm again, lie sideways across a flat bench, so neither prone nor supine. Then, simply tilt your body toward the floor at a 45° angle, so toward more prone. Looking downward can help to facilitate this while maintaining the position.

This motion feels great, almost like a machine-based reverse fly, though without as much tension at the endpoints.

Keep the arm perpendicular to the bench to maximize transverse abduction. Sweep your arm out to focus on rear delt versus scapular retraction for the middle trapezius. A slight bend of the elbow is fine.

While some research favors a neutral grip, either neutral or pronated should be fine.

Like the lateral raise for abduction, a more supine position here would overload the rotator cuff, in this case the teres minor and infraspinatus, versus the deltoid because of the shifting moment arms.

Though perhaps less stable, this is also possible with a cable machine, standing while tilted away from the stack. This could also be done with both arms, like a face pull or reverse cable crossover, though the asymmetry can have the movement feel uneven.

Front Delt: Incline Dumbbell or Cable Front Raise?

Stretching and working the front delt already occurs to some extent on horizontal abduction or flexion, so exercises like the incline press.

You could also perform a front raise while leaning back against a wall, on an incline bench, or with a cable machine just like the lateral raise.

As mentioned, overhead pressing works so well within the context of a whole program because it also hits the serratus, despite lacking the 45° angle described here. It fails to address the front delt best, yet this muscle tends to receive plenty of work already.

Overloading Lower Angles for Impressive Shoulders

It is not enough to do your best; you must know what to do, and then do your best.

– Edwards Deming

The most important concern to work a muscle is to address its main functions. This means abduction for the middle deltoid and transverse abduction for the rear deltoid. Flexion best emphasizes the front deltoid, though horizontal adduction hits it too.

We then want to have a dominant moment arm relative to other active muscles. Again, this means not too low when focusing on the deltoid. (Keep in mind that the moment arm concept could be applied to emphasize the rotator cuff muscles, if so desired.)

Finally, without neural inhibition as a possible issue, we need to maximize the force potential of the working muscle by overloading it at medium lengths, meaning lower angles.

Working close to failure then fatigues slower-threshold motor units while slowing the movement enough to require high tension from the fast-twitch muscle fibers, or those most responsible for muscle size.

Thinking about this logically, our deltoids evolved to hold objects away from our sides, not to generate large forces throughout a range of motion. They are stabilizer muscles when force is needed, otherwise meant for mobility.

Within a bodybuilding context, we still need movement to stimulate delt growth best, yet it’s sensible to consider this context.

Finally, if there’s an ideal overload position, you may ask why should we move at all? (This also explains why we don’t just perform a normal lateral raise with less range of motion.)

You need enough range of motion to muster power for the ideal portion. Other positions address different muscles due to the interplay of various moment arms. Speculatively, they may even hit non-uniform sarcomeres throughout the fiber more or less optimally.

Without enough movement, exercise becomes quasi-isometric. This limits goal-based effort and passive tension from the negative portion of the rep.

So, try overloading your delts at 45° using the lateral raises described here. You’ll find a deeper soreness within them afterward, impossible to attain otherwise, that comes from working them at stronger lengths. This better stimulation will surely lead to wider, more impressive shoulders.